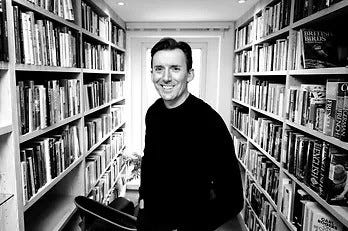

James meets... Jonathan Wilson (Football Writer)

An interview with the legendary football scribe on the Charlton brothers, Super Leagues, and dreaming of getting drunk with Norman Mailer.

To those of us who watch football matches in black and white on our days off, Jonathan Wilson represents everything you could want football journalism to be: intelligent, political, serious, but always entertaining. His books are the north star of what it means to write about the historical importance of football and the amazing stories this sport has produced over the last century.

I spoke to the very friendly Jonathan over video in September 2024 to talk all things football, his latest book Two Brothers: The Life and Times of Bobby and Jack Charlton, and an unexpected introduction to the history of 1950s post-colonial Africa.

James T: When I interviewed you before, the first thing we spoke about was the Super League and you talking about how you thought it was inevitable. And then, obviously, since then, it's become "evitable," if that's a word. So I remember seeing the news, and it's one of those times when you feel shocked but not surprised. I wasn't surprised that it was happening, but I was a bit shocked like: Oh my god, they're actually doing it. So do you remember where you were when you got the news, when you saw it, and how you felt?

Jonathan Wilson: I honestly can't remember where I was, but it was so obviously flawed right from the start. I thought this cannot happen; they've really messed this up. It's really odd; if you're gonna launch something like that, you need a PR campaign beforehand to soften people up and say, “the modern state of football is a disaster. This isn't working. We need change.” You drip and drip that out, and then once you sense the mood is ripe for revolution, that's when you strike. Not this sort of really half-arsed document that didn't really make sense.

And then there's some very odd stuff going on in the background with this. I think it's fair to say that the organisers believed Boris Johnson would back it. I'm not going to tell you who the people involved are. You can trace very easily who in Boris Johnson's close circle of advisors may have worked with a club CEO at a previous point. Now, that club CEO, who's no longer in position, denies having anything to do with it.

JT: Yeah, of course.

JW: You will also find that in No. 10s diary, a couple of weeks before that, there is a meeting scheduled between one of Johnson's advisors and a senior Premier League CEO. They claim that what was discussed was the return of fans after Covid, which is possible. It's interesting that they only spoke to one club CEO about that and not Richard Masters. And what then happened on the Monday morning was that a senior civil servant close to Johnson, who is a big football fan, a genuine football fan. And Johnson said to him, look, you like football? One word: good or bad, Super League? And he went bad. At which point Johnson apparently went, Right, we're not backing this; it's too unpopular. So that obviously was a crushing thing for the Super League. I'm not saying that with Johnson's backing, it would have gone ahead, but it would have been a lot easier.

JT: But do you think they actually meant it, or was it just a proxy to get the Champions League format?

JW: No, but I do think that they were aware that the worst-case scenario was to put pressure on UEFA. I think the fact that [UEFA President] Aleksander Čeferin is so inclined to give the big clubs what they want, he doesn't want to take them on. At heart, the big clubs all want more money, and Čeferin seems very reluctant to fight on behalf of smaller nations and smaller clubs, or any sense of competitive balance.

JT: Does anyone actually have either the guts or the political power to actually reform football in a way that will move us away from the Super Club paradigm? Because the only way I can see that it could move away is forced redistribution of wealth. But any kind of move towards that, they probably will just break away, won't they?

JW: I mean, I think taking on the big clubs would be a massive risk. They're very powerful. And it's not just that the clubs are run by rich people who are used to getting their ways, but in some cases, they're run by [soverign] states. I think we've seen, for instance, with Manchester City's cases, first UEFA, then the Premier League, that they are very prepared to spend a lot of money on taking legal action against the football's ruling authorities. And football's ruling authorities don't have that much money to fight back. To take on a major petro-state is very, very difficult. People just don't have the resources. It feels, with the City case, we are reaching some kind of crisis point. Whichever way the decision goes, there's a potential existential threat to the Premier League: that either City are found guilty and get an enormous punishment. And it's hard to see if they're found guilty of many [of the charges], the punishment wouldn't be enormous, but you assume they would then appeal, and there would be lengthy legal action, which the Premier League might not be able, or might not wish to, afford.

But equally, if City are somehow let off, if they are found not guilty, if there's some technicality found, then I think there's [going to be] a lot of anger among the other clubs, and if action is not taken, I think those clubs might then take legal action. There are some briefings happening that clubs might look to break away from the Premier League and return to the EFL. Now, I think when push comes to shove, that’s quite unlikely. I think Newcastle and Aston Villa, for geopolitical reasons, are inclined to back City. That leaves 17 Premier League clubs. If you're one of the bigger clubs, are you going to risk killing the golden goose? If you're one of the smaller clubs, you're getting a fortune for sitting in 13th, 14th, or 15th. Are you going to risk that? So I think the threat to return to the EFL, is probably just a threat, but it's worth the Premier League bearing it in mind that that's a danger.

JT: It seems that we're heading towards some kind of nuclear war. I mean, would they really relegate Man City, and I also don't really understand that punishment, like, so you relegate them to the Championship. Why? Why just the Championship?

JW: Well, the relegation is not possible. Expulsion is possible.

JT: Right, okay.1

JW: The Premier League is essentially a private members club of 20 members. And if the other 19 or more than two-thirds majority decide that one of their members has ridden roughshod over the regulations, as with any private members club, the other members can vote to expel a member. The issue then is for the EFL to decide if and at what level they would accept that. It's not a case of relegating them. What they could do will be to de facto relegate them by docking them 100 points.

JT: It would be quite fun to see them in League Two; it would be like a Football Manager database hack. But it's interesting, kind of combining this with the Rodri and Alison interviews recently about the potential to strike. There was an article on the BBC about whether it was possible; it was about a thousand words long and it could have been three words long: Fuck knows, mate. But do you think there is an element of 'if the players want to play less, they’re at some point going to have to accept earning less money, but it doesn't really seem that that will ever happen?

JW: Yeah, and you've also got the issue that players earn vastly different amounts. So, you know, if you're a Rodrigo and Allison or a player at a top club, you might think, you know what? I'd rather play 80% of the games [for] 80% of the cash. If you're playing in League One, you're probably going: give me 120% of the games, 120% of the cash, and I'll take that grind on my body because I want the money. So I think that's one of the issues with a strike.

JT: I do think there is too much football or there's not enough of a break. And this makes me sound really old, but I do remember summers without a tournament, the only way you could see Leicester’s friendly results was buying the Leicester Mercury. I do wish we still had that, because a break is good. The authorities just think that more and more is the way, is better, but it isn't. Across all sports, like cricket, golf, everywhere, they just want more and more.

JW: I find myself; the way I consume cricket now, is okay; if it's a major Test match, if it's England vs. Australia or India, I make a point of finding out what's going on. Otherwise, if it gets to sort of 4 p.m., I'll just flick it on, have it in the background, just to give my eyes something else to do. This England Australia ODI, why are we playing this in September?

JT: I thought that the other day, I didn't even know it was happening.

JW: They devalue the Test matches [as well]. The Sri Lanka and West Indies games again, I sort of kept up with them, but I wasn't sort of glued to them in a way that I used to be for Test series.

I feel a bit like that's what the Champions League is going to be like. And it's also because the. Just the nature of the format is, and maybe this is a nerds point, but it's impossible to keep in your head who's playing who at what point. Nobody can with 144 fixtures. Whereas if you've got eight groups of four, I know that Real Madrid are in a group with Sparta Prague and Lille or whatever. And so you've got some idea of what's going on. Whereas with this, I know that Arsenal are playing tonight but I don't know who's playing who next week. It's impossible to keep up with.

Thanks for reading James on... Everything(ish)! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

JT: So let’s talk a little bit about Two Brothers, your twin biography of Bobby and Jack Charloton published in 2023, which was very good, obviously.

JW: Thank you.

JT: Why did you decide to write a book about those two people, considering that they've both been written about quite a lot? Where was the starting point?

JW: I was playing cricket in the authors against the publishers [match]. I was fielding at square leg, chatting to the umpire. He was a publisher, and he said, - where are you at in your career now? What are you up to? And I was like, not really getting anywhere. And then two weeks later, he emailed my agent, who was also playing in the game, and said, “what do you fancy doing a joint biography of the two Charltons?” And my initial reaction was, really. And then the more I thought about it, maybe they haven't really been put properly into historical and sociocultural context. I think. I'm not even sure Bobby, after Munich had been done,. [There’s] obviously a lot of stuff on Munich, and a lot of it's very good, but I think a lot of stuff around Bobby is sort of slightly skirted over what happened. And I mean, amazing details. The night before the World Cup final in '66, Alf Ramsay takes the team to the cinema to see Those Magnificent Men in the Flying Machines. So Bobby Charlton, who's terrified of flying, is forced to sit through a film about people flying old planes. So that kind of detail, I think, hadn't really been gone into.

Jack's stuff with Ireland has been gone into quite a lot, but his early managerial career, his time at Middlesbrough, Sheffield Wednesday, even Newcastle, hadn't really been gone into. And so that's sort of where I focused the primary research. That's where I did the interviews. And obviously a lot of people who played with them have either died or their memories have gone. But people who played for Jack in the 70s or early 80s, and a handful of people who played for Bobby at Preston, are still perfectly capable of being interviewed. And I thought there is actually something there.

JT: And I think one of the interesting things is that obviously Jack does go down the pits. Not for too long, but he's -

JW: He’s in for one day.1

JT: Ha! I thought he worked down there for longer.

JW: No, he worked on the surface for a while, but his first day down the pit was what [persuaded him] “No, this is not for me. He has some job like weighing the coal that comes out or something and checking the quality.

JT: Obviously that's a workplace where death was normal and Bobby was kind of separated from that. But then he goes through one of the worst deaths in the workplace that you can kind of imagine. Do you think that initial separation from that world and Jack's immersion in that world, however superficial, shaped who they were?

JW: Possibly. I think Bobby knew very early on he's going to be a footballer, but I also think it piled pressure on him, and I think he really felt the pressure. He knew he had a great gift, but he felt he really had to make the most of that gift and give everything to use that gift to its maximum. Of course, that's only heightened after Munich. It's his responsibility too, as he sees it. Duncan Edwards and Liam Whelan and all the others, [they] haven't had the chance to make the most of their talent, whereas he has. And so I think he really feels the pressure of that. He is somebody. I think he's a naturally anxious person, and he gets very anxious before games. I mean, he would have a nip of brandy before games all the way through his career to calm himself down.2

Whereas Jack is more; I can't believe they’re letting me do this. And I think Jack's just a much more bluff, confident figure. But I think for him, football was a bonus. It's like, well, I don't have to do a proper job. I'm not saying he doesn't take it seriously because he clearly does. But he doesn't feel that crushing sense of responsibility that Bobby does.

JT: I don't think Jack was necessarily like a raging militant socialist, but he obviously had the famous quote about how he would be striking with the miners in 1984. And I think that Bobby seems to have been the kind of working-class voter that Thatcher attracted. Did that play a big part in their relationship? And was that a difficult thing for them?

JW: I doubt politics was a thing that divided them, but I do think the politics is reflective of temperamental differences that divided them. Yeah, I mean they're very, very different people. And the cliche is, or the stereotype is, Bobby was cold, a bit distant, hard to get to know, whereas Jack was open, ebullient, and charismatic. There's an element of truth to that. But equally, I heard loads of stories of Bobby being incredibly kind for no reason, just because he could be. And there's still times when he snaps at the kids asking for autographs; that does happen. Obviously, that's not great. But all of us have bad days, and Jack equally behaves very badly at some points.

I think you're right that Jack was instinctively for the workers, socialist type. In his own career, he was always arguing for his own advancement, asking for more money, asking for more responsibility, asking for better facilities, better conditions, which he then doesn't give to his own players at all.

Whereas Bobby, I think he is a more thoughtful, reserved figure. I would say he probably was a Daily Mail reading conservative.

JT: And obviously because it's a book about Britain in the second half of the 20th century, class is right at the centre of the book. And I think that even though class is the most important factor in determining someone’s life chances, it's kind of been replaced now by maybe race, gender, the culture war nonsense that we have to live with. But in that period, it was the kind of defining social culture war, for want of a better word. We just had this report about how only 7% of the people in TV and film are from a working-class background. Football has always been seen as a working-class sport, and it's been seen as almost like an escape for working-class people. Do you think that's still true now?

JW: Probably less so. Football is one of the rare industries; it's maybe less so now than it was even ten years ago, where the prejudice goes the other way. I think there was definitely a time that it was quite hard for middle-class people to make it as a footballer.

Is it still an escape? I mean, it's definitely an escape if you were brought up in a shanty town in Lagos or something. Maybe less so in the UK. But I mean, the point you make about class having diminished, in terms of our awareness of it, I think that is definitely true, and I think that's really damaging. I think class remains one of the greatest divides and obstacles. That 7% you mentioned or the number of cricketers from state schools, [which] is incredibly low. I know all of that is very damaging, very dangerous.

JT: I didn't go to a school that had a cricket pitch.

JW: (Laughs) Yeah, I mean, I went to a posh school, so I did. It's a very damaging phenomenon. I think that one of the problems is that [class] is not as visible as race or gender, and therefore I think it often goes unnoticed. But obviously, particularly [with] race, it's often intertwined.

While I think there are still prejudices there in terms of managers and owners, and clearly there is still racial abuse, particularly online, very occasionally in the stadiums, but in terms of on the pitch, I think football is pretty much as colourblind an environment as you are likely to find. I don't want to say there's no racism in football. As I say, I think there are areas where it does exist, but on the pitch, in the UK, it's pretty much as good as it gets in any sphere.

JT: Over the last year or so, I've probably written like half a dozen stories about the gambling industry in football. This is not a criticism at all, but I know you have done some work in that area, giving out tips and stuff via videos on Twitter. And I was wondering where you stood on gambling's relationship to football. If you are as dogmatic as—I would be in line with Philippe Auclair—that there should be no relationship, at least no advertising or anything. So I was just wondering where you stood on that?

JW: I think the regulation should be tightened up. Absolutely. A lot of people have a moral problem with gambling, which I don't have. I think if you don't have gambling regulated, it becomes a bigger problem. If you look at countries where gambling is illegal, for instance, gambling on the IPL, it's massively problematic. Gambling is much better when it's clear and open. And the gambling industry provides a very good safeguard against match fixing. So on a practical level, I think we need to accept it's going to happen, and it's much better when people are gambling with legal bookmakers who are regulated.

However, I think the area where football does have a problem, and it's what you hinted at in the question, is the advertising of it. If somebody's an alcoholic—we're quite happy with a world in which somebody can be an alcoholic; the alcohol has caused them a problem, and yet pubs exist. Those two things are fine because it's not that difficult [for the] alcoholic to avoid the pub.

JT: True.

JW: Whereas if you're a gambling addict, I think you should be able to sit down and watch football on a Sunday afternoon without a gambling advertisement coming on the TV before kickoff telling you to go on the app on your phone. That is the equivalent of somebody walking past an alcoholic with a drinks trolley. I think football has a responsibility to, as far as is reasonably possible, separate addicts and people who have the potential to have a problem with it, from the industry itself. So I don't think it should be difficult to put a ban on television advertising of gambling in the 30 minutes before kickoff or the hour before kickoff.

With shirt sponsors, I don't think it's a good look when, for instance, kids are walking around with betting companies on their chests. So I think that's something else that could be regulated. I think that is being phased out by the Premier League.3But they can clearly go further. Fundamentally, I think [gambling] will happen, and we should accept it's going to happen. And it should be open and regulated, but we should also be conscious of who we're marketing it to, and it shouldn't be marketed to kids and people who potentially have an addiction issue.

JT: You're the editor of the wonderful The Blizzard magazine.4 What do you think makes a good pitch? And what is it that new writers or freelance writers get wrong when they pitch to you?

JW: There's a couple of really obvious things that people get wrong, like if your pitch is full of spelling errors and grammatical errors.5

JT: Do you get that a lot?

JW: Oh yeah. Or if you get my name wrong.6 I've got limited time when I get your copy. I don't want to have to spend hours and hours just putting it right. Show me you can actually do the job and you respect the magazine enough to bother to make your pitch [grammatically correct]. You don't have to jazz it up with pictures, but at least spell the words right.

I'm not sure there's any hard and fast rule. I basically go on my gut. Does that sound interesting? It only has to be three or four paragraphs long. You don't have to go into any great depth. Just tell me: what's the subject matter? What's your angle on it? What are you going to do? Who are the people you know, or who are you going to talk to if you need to? Just show me your approach and show that you have some notion of what The Blizzard is. So don't pitch something like “Everton’s five best signings.” That's not what we run. Don't pitch something that's 800 words long, and don't pitch something that's 40,000 words long. Look at the kind of length of stuff we run. Look at the sort of approach we take.

I don't think there is any great science to it. Just three or four paragraphs setting out this is who I am, this is what I want to do. This is the angle. This is why it's appropriate to you.

JT: So I'm going to ask you a bit of a stupid question to finish off. I'm putting some caveats on this one, though.

You've got a T.A.R.D.I.S.; you can fly it. The translation matrix is working. You've got your psychic paper, so you can get into anything. What three football matches are you going to? However, I'm not letting you pick the 1973 FA Cup final7 or the 1954 World Cup semi-final8 because I imagine those would be two of them.

JW: Yeah, they probably would have been. Well, I think the 1930 World Cup final. To go to the first World Cup final, the fact that it's Uruguay vs. Argentina, supposedly a very hostile atmosphere, although accounts about that vary. So I think that would be a great one to be at. What else?. I mean, it's not a football match, but the thing I would love to have covered would have been the Ali vs. Foreman fight in 1974.

JT: Is that Manila?

JW: No, Kinshasa.

JT: You can have that; why not.

JW: So all the stuff about [DRC dictator] Mobutu, all that sort of craziness around that fight. At that point, it was by far the biggest sporting event ever held in Africa. And the fact that Foreman gets a cut on his eyes and the fight is delayed for six weeks and everybody just hangs around for six weeks. There's all these stories about George Clinton and Norman Mailer just going out on the piss every night. Or Ali, you’d obviously get to know him really well because he’s just got along to the gym every day. I think James Brown is there and gives concerts every night. I'm not sure it's the full six weeks, but he gives a series of concerts because they are desperate to fill time. The rainy season is encroaching, and they’re really worried that they're going to have to call off the fight. Literally the night of the fight, just as it finishes, the heavens open and the rainy season begins. I mean, whether setting myself up to write a book to take on The Fight by Norman Mailer is a great idea, I'm not sure, but what a thing to write about that would be. And going drinking with George Plimpton and Mailer, that would have been great.

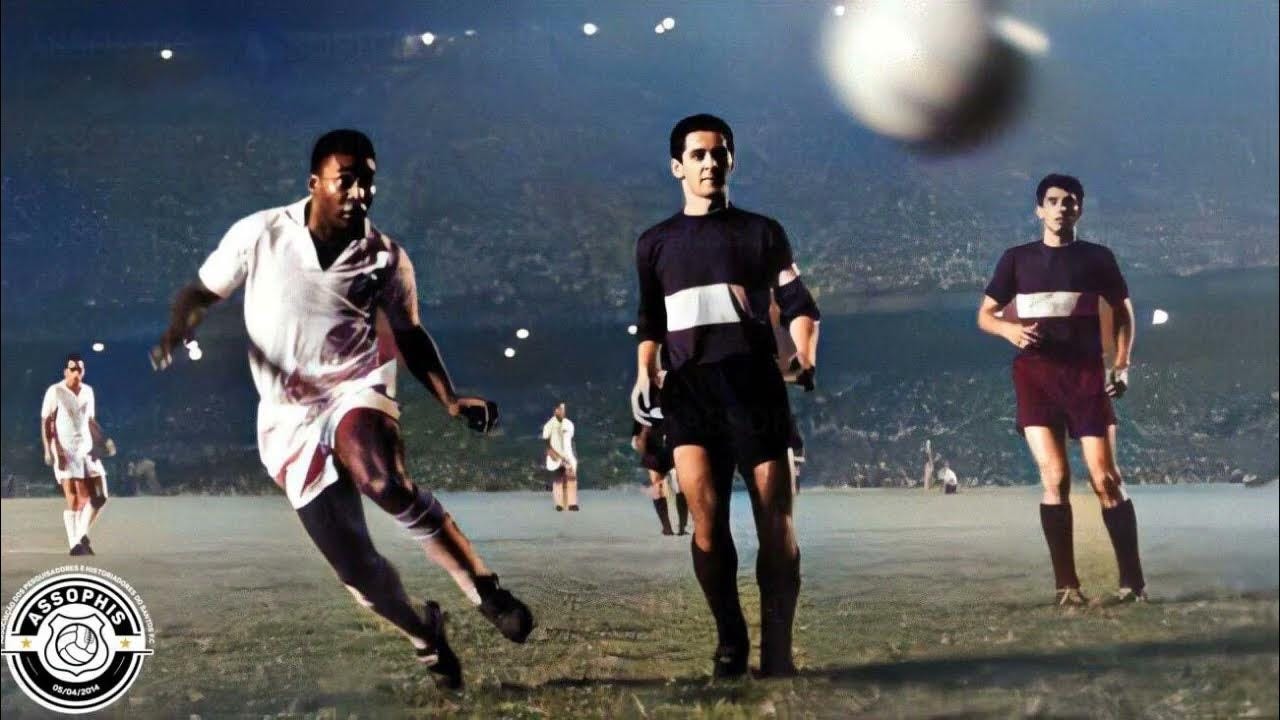

Maybe this is a little bit kind of an adjunct to the Rumble in the Jungle, but there's a series of games in the late 60s between a team that at the time was called "Tout Puissant" Engelbert, which are now TP Mozambique from Rubumbashi in the DRC. [I’d love to have seen] their games against Ashanti Kotoku of Ghana. And I think they met either three or four years in a row. They met in either the semi-final or the final of the African Champions Cup. So they developed this amazing rivalry. Weirdly, Castlebert Pereira is coaching Chalikotulka for one of those games. He's in his late teens. He goes from Brazil to Ghana. You've got Bob Mensa in goal. He's killed in a bar fight in 74. I think he's the great goalkeeper, the great tragic hero of early Ghanaian football. But I think that period, when you've got Africa coming out of colonialism, I guess by then [Ghana’s first President after independence] Kwame Nkrumah has gone, but you’ve still got Nkrumah's legacy; you’ve got Mobutu in the DRC, well, in Zaire, as he called it. And yet Lubumbashi was where [first President of the independent DRC] Patrice Lumumba was from. There's so many complicated political stories. So I go back in the T.A.R.D.I.S., I cover those games, and I hang around for six years and do the Rumble in the Jungle.9

JT: Yeah, nice. Actually, when I asked Michael Cox that question, he picked the 1970 World Cup final. But he made the point that in order to fully enjoy it and appreciate it, you'd have to spend the year watching English First Division football, and I'm not entirely sure whether it'd be worth it.

JW: I mean that World Cup final; the odd thing about that is that it's celebrated as being the apogee of the game. And yet, the Brazilian government's really quite unpleasant, and that Mexican government's really quite unpleasant. You had the massacre of the students in Mexico City two years earlier, just before the Olympics. They're a CIA-backed dictatorship, and they basically commit one atrocity. But it is a really big one where they [killed] 500 students. But I wouldn't mind going; it'd be nice to see Coxy in Mexico City.

I think there's two other options. So covering the Santos vs. Boca Juniors Liberdadores final from 1963—oh, actually, maybe Benfica winning the European Cup for the second time when they beat Real Madrid in 1962. You get Bella Gutman on the bench, and you get Puskas playing midfield. Or maybe AC Milan beating Real Madrid 5-0 in the second leg of the European Cup semi-final in 1989. (Laughs) I’ve given you five answers there.

Jonathan Wilson is the author of 13 books on football, contributes to The Guardian, World Soccer, and UnHerd, as well as editing the quarterly magazine the The Blizzard and hosting the new podcast It Was What it Was.

Find out everything about his work here:

https://www.jonawils.com/

Jonathan Wilson is the author of 13 books on football, contributes to The Guardian, World Soccer and UnHerd, as well as editing the quarterly magazine the The Blizzard and hosting the new podcast It Was What it Was.

Find out everything about his work here: https://www.jonawils.com/

I leave these mistakes in so you can see just how much of a chancer I am.

Other grounding methods are available.

While this is true, and any progress is still progress, the ban is literally only related to the front of the shirt. Clubs are still allowed to advertise gambling companies on the back of the shirt, the sleeves, and anywhere else in the stadium.

My favourite ever Blizzard piece was by Simone Pierotti about Shostakovich’s football obsession, which is available in Issue 35.

I’d like to state for the record that my rejected pitch did not have grammar or spelling errors. I think. I don’t dare check.

I definitely haven’t done this when emailing editors. No sir, not me, never.

When Jonathan’s beloved Sunderland beat Revie’s Leeds 1-0.

I basically have no idea what any of this paragraph means.