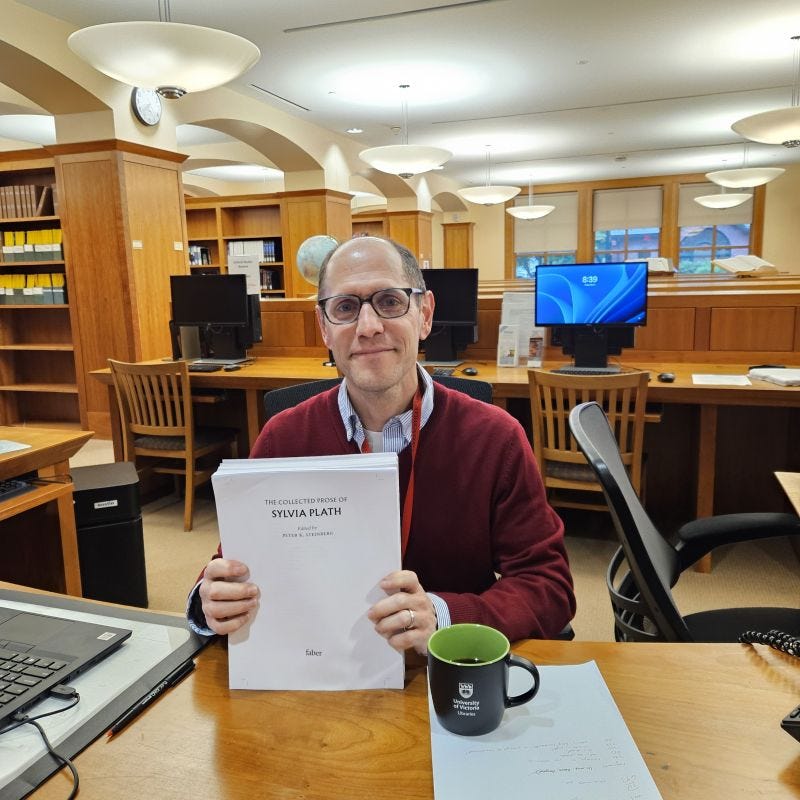

James meets... Peter K. Steinberg (Sylvia Plath Editor and Archivist)

I talk to Peter about editing Plath's Collected Prose, archival research and why the 1979 adaptation of The Bell Jar is so bad you need to watch it mashed.

Peter K. Steinberg is the editor and author of numerous books on the life and work of Sylvia Plath, including The Collected Prose of Sylvia Plath, published in September 2024.

I spoke with the brilliant Peter over video call to discuss this new publication, how so much of Plath’s writing still remained unpublished and her utter despair at mid-20th century English plumbing systems.

James: I thought we’d start at the actual start. So how did you become involved in working in the Plath archive and kind of becoming the main man, as it were, with the archive?

Peter: Well, so I first read Plath in 1994 in a poetry class that I took in college. It was just a sort of Introduction to Poetry class that I had decided to take. I guess I was a junior, so I was in my third year. I had recently had my heart broken by a girl, so I said, Well, I should take poetry. Poetry will help. And we got to Plath, and we read Lady Lazarus. And it was really the first poem that I read that sort of spoke to me, and it just made me realise I will get over the girl and I will come out on the other side. So I asked my teacher for more information about Plath, and he said, I really don't recommend you read her.

James: Why did he say that?

Peter: He didn't like her.

James: Oh, right, fair enough.

Peter: And that's fine. But the thing that I had a problem with was that I was not a good student. And here I was finally finding something that I could be interested in, and I got shot down. But my friend and I went to the library. We got the Plath books, and now it's 30 years later. That's sort of how I got into Plath. Then, as regards the archive, I befriended a man called Jack Folsom through this old Sylvia Plath forum website that was run out of Hebden Bridge. This was right after Birthday Letters came out.

James: So there was a Sylvia Plath forum on the Internet in 1998?

Peter: Yeah. It started in response to Birthday Letters.

James: Wow, that's amazing.

Peter: I was pretty new to the Internet, as were many people [but] it was just this wonderful place to go. At first to talk about the Birthday Letters, and then it kind of grew from that for several years. But Jack Folsom and I started a conversation, and he encouraged me to go to Smith College to look at the archive there. So in May of that year, I drove up to Massachusetts from Virginia and fell absolutely in love with the archive and the idea of the archive and that really kind of got me going in a direction.

James: Do you remember kind of how you felt when you first saw her handwriting or her typescript on the page and kind of what that meant and how you felt?

Peter: The day before we got to Smith College, I walked around the library and figured out where the rare book room was, because on the next day, in the morning, I kind of wanted to know exactly where I was supposed to go beyond that. I had never worked in an archive before, so I didn't know what to expect. But I had a dream that night that I was back in the library, walking up to the rare book room, and I ran into Ted Hughes, and I said, I'm sorry that I'm here. And he goes, no, don't worry. You're fine. It gave me some sort of validation for the imposter syndrome that I was feeling. I don't know if imposter syndrome was a thing in 1998, but that was something I was feeling. Then the next day, when I went in, I met Karen V. Kukil, who, if she wasn't already, was just about to be editing [Plath’s unabridged] journals.

James: You met her on that first day?

Peter: Yeah, she sat me down, and I looked at Plath's original journal, the one from 1950 to 53. It's all handwritten, and I just went through it, looking at the real journal, and I brought my copy of the abridged journals with me, and I was just writing in the stuff that the editors had cut out. Then she showed me her dictionary, and so I was able to look at the words that she was looking up, things like that.

James: Plath’s own dictionary?

Peter: Yeah, yeah.

James: That’s really cool.

Peter: It's an amazing document. All the words she looked up that she was using for her poetry, her prose and papers, and things like that. That initial response and feeling to being in the archive was just one of comfort, home, and excitement. I remember looking at drafts of poetry [for the] two or three days I was there, and I fell deeply in love with archival research at that time.

James: So what is the kind of technical process that goes from the kind of handwritten or the typescript to this? Are you, like, having to type them all into a Word document?

Peter: To begin at the beginning, the first thing was to identify everything. That meant going to various archives or working with the finding aids that are online and just compiling lists of poems and lists of prose. So it was identifying everything, getting copies of everything, scanning everything to PDF or getting a jpeg of it, and then, yes, creating Word documents, creating thousands of Word documents between the letters and all the works that are in the prose book. So I type everything and I proof it in Word, and then I use whatever the feature is called in Word, where I just combine everything because I have everything filed in date order, and then I can just add objects using that feature.

James: In the preface, you say that you started compiling in 1998. When did you actually get the commission for this? And how long have you been kind of knowing that it was going somewhere?

Peter: Well, that sort of happened during the process of doing the Letters of Sylvia Plath, where I got copies of all the things I didn't have. Because if Plath was mentioning them [the prose pieces], I needed to have them at hand so I could footnote it. Around 2015, I had been transcribing everything, too, just because it's easier for my computer to remember things than me. I sort of realised, Oh, I have everything transcribed. This could be my dream book. Back in 1998, I read short stories that weren't in Johnny Panic. I was really surprised. I mean, I was so new at the time, I didn't realise that even though the cover of the book had "Selected Prose”, it didn't hit me that there were things excluded.

James: Yeah.

Peter: (Laughs) Which is kind of embarrassing! So at that point, I thought, well, I'd love to see everything in print. In 2015, that's when I made the first draft of the book, sort of contemporaneously with Letters. I started talking to Frieda Hughes about the prose book, and she seemed okay with it. And it wasn't until late January of 2022 that I actually got the contract. So it was a long process, and it was kind of tricky, or risky, I guess, is the better word to make a book with no contract.

James: Yeah I can imagine.

Peter: But it's a book I've wanted to do for a long time, and I think it was a book that was overdue. I did some math, and until this book came out, about only 13 or 15% of Plath's prose had been published.

James: That’s mental.

Peter: This book is about 85% more than anyone any casual reader who can't get to an archive would ever have access to.

James: So, off that 15%, I'm guessing a big chunk of that is Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams, the original publication?

Peter: It's all Johnny Panic. And then Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom in the 90s.

James: I didn't really know anything about her nonfiction writing, and I'm a big fan. You mentioned Frieda. I was wondering what your relationship is with her and how that interacts with putting a book out like this. Does she have to give the okay?

Peter: She owns the copyright to this stuff, so she does have to approve it, and the contract wouldn't have been issued without her approval to begin with. She was really awesome to work with. I've only ever emailed her. I've never met her in person; she's always been really gracious and sweet and supportive. And, I think, happy with the stuff that I've produced.

James: In your conversations, was the stuff in here that she'd never read or never seen before?

Peter: I'm confident that most of that stuff she didn't know about. Generally, the way the Plath archive works is: Indiana University has its strongest in anything created before 1960, when Plath was living in Wellesley for the most part, or she was storing stuff in her mother's house. So when she moved to England permanently in late 1959, anything that was left behind, plus all the hundreds of letters that she sent home after that, were in that house in Wellesley. And that's largely what Aurelia Plath sold to Indiana. Then in England between London and Yorkshire and Devon, anything that Plath retained there, Ted Hughes then sold to Smith College or Emory University later on in his life. So that's kind of how they're broken down. And then there are smatterings of Plath at 55 other different archives, not to mention personal collections. So there is stuff everywhere.

James: When you consider she didn't publish that much, and she died very young. She's one of the most written-about writers, maybe not of all time, but certainly the last 30, 40 years. And for us to be in a position in 2024, where an 800-page book is released of unknown stuff is really amazing, isn't it?

Peter: I can say with certainty that part three, the Smith College press board stuff, [Frieda] never would have seen, because Plath herself didn't even save copies of the typescripts or clippings.

James: So that's all taken from microfilm and microfiche in the newspaper records?

Peter: Yeah, there are a few typescripts that exist at the Smith College archive, so anybody who's gone to look at the Plath stuff there might have seen her typescripts, but the actual newspaper articles or the transcriptions that I made from them know no one had ever seen before.

James: So are we kind of now at the point where pretty much almost everything she ever wrote is now in the public realm? Creatively at least.

Peter: I do know that there are some letters out there that we don't have access to. There are some short stories or fragments of short stories out there that I couldn't get access to. There is a new, complete volume of poetry that's in the works right now. I think that's scheduled for next spring.

James: So it's going to have more stuff in it than that Faber Collected Poems that was published in 1981?1

Peter: It's going to have almost two-thirds of new content.

James: How is that even possible? It seems crazy to me, just because of how famous she is and how beloved she is, that we're still here and we're still finding new stuff.

Peter: A microstory about that is when Ted Hughes put out Johnny Panic in 1977; at the same sort of time, Aurelia Plath was in the process of selling the archive to Indiana University. Ted Hughes didn't know that the stuff was there, so he found out that Aurelia was selling everything to Indiana. Somehow he got copies of a lot of stuff, so when Johnny Panic came out in paperback, it included four stories that were now held at the Lilly Library at Indiana University. So that's kind of why. I mean, Ted Hughes was doing all this work from England, but he didn't really have access to any of the stuff in Wellesley. And then, at the same time, there were tonnes of stories in all of Plath's early poems that Aurelia Plath had in the house. Hundreds of poems from before 1956 that Ted Hughes didn't really know about. So in Collected Poems, there are 50 Juvenalia poems.

James: It starts when she meets him, doesn't it?

Peter: Yeah, and then tucked in the back are 50 earlier poems. Those were just poems selected from the huge amount of poems that Auerila Plath had that he didn't have.

James: I'm so happy that this book exists and that the journals and the letters exist and everything. Do you think there's a moral element of—should all of this stuff exist? Is it right that almost every single word ever wrote, or at least much more than the average writer. Could it be argued that it's not necessarily wrong, but there's something either odd or maybe voyeuristic about printing everything that this person ever did?

Peter: That's a good question. I'm not sure how to answer it. There are certainly weaker pieces in there, in the book that just came out, and there are weaker letters. One of the things that Letters Home tried to do was to -

James: Or should we even be thinking about this person's letters as strong or weak? They're just letters she's writing to a Mum or a friend.

Peter: I don't have a problem with everything being printed, but I do see the argument that some might not want everything printed. I'm thinking in particular of the love letters she wrote to Ted Hughes or the letters that Plath wrote to Doctor Beuscher. Are they sort of the psychiatrist/patient working relationship, or are they just general correspondence?

James: I suppose I asked that question partly because Ted Hughes obviously gets a lot of criticism for his behaviour towards Plath and their relationship and everything. And quite rightly, in many cases, I think. I'm kind of asking it because of that, that decision to destroy the last two years of Plath’s journals. People are very critical of that, and I kind of understand it, but at the same time, I do kind of think, Well, they're his children; it's his family. We all make those kinds of decisions in our own lives all of the time. Just because she is famous and we love her doesn't necessarily mean that we should get to see that stuff.

Peter: Yeah, I don't disagree with you. There is an element of voyeurism; I would put it more voyeuristic in terms of the private writing than I would the creative writing. The creative writing might not apply necessarily to the earliest pieces, but certainly, the later pieces were written with the intention of being published.

James: Yes, absolutely.

Peter: You know, she sent almost everything she wrote out after a certain point. So I look at those as being a little bit different, perhaps, than private writing, like a letter or a journal. And those journals, the late journals, were not destroyed. They do exist.

James: I thought they were destroyed?

Peter: He wrote several different things. At one point he wrote, he destroyed it. At one point it was said that he only destroyed the last page of the last journal. And then there's a letter that he wrote to Jacqueline Rose, or a draft of a letter that he wrote to Jacqueline Rose in his letters book, where he admits that he didn't destroy anything.

James: So does Frieda have them?

Peter: I do know where they are, but they're not accessible.2

James: Yeah, and I suppose whether they should be or not is what we're talking about. And as much as I would love to read them, I also understand why they aren't accessible because I imagine there's very difficult stuff in there.

Peter: I've actually never had any issue reading Plath’s journals or her letters, with the exception of things that have to do with sex. That's the one thing that I'm just completely uncomfortable knowing. Otherwise, I just try to look at everything as to how it might help elucidate some of her writing. And then biographically, I find her a fascinating person. Biographically.

James: Absolutely. Yeah.

Peter: So in that regard, I am the peanut cruncher that she chastises in Lady Lazarus.

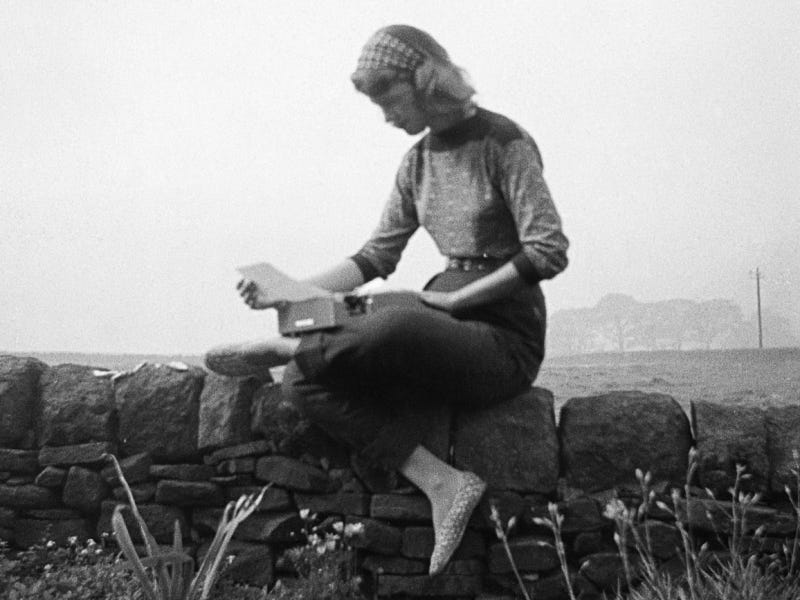

James: Was Plath a very meticulous organizer of her own work?

Peter: She was thoroughly professional, probably by the time she entered high school. She has these submission lists that she kept from late high school through the end of her life. She typed the name of the journal, the name of the works that she was submitting, the date she sent it and the date it was accepted or rejected, and how much money she earned. She was completely on top of that.

James: Are we kind of reaching the end point of her printing her work now?

Peter: I think so. I suspect at some point that there will be more letters that will come out, but I don't know how you would weave them into a book like The Letters of Sylvia Plath. You’d probably have to treat it like a book of poems and do a New and Selected Letters. There are going to be new poems, I'm sure, that come to light at some point. Obviously, the journals; it may be 2063 before we get access to them, so live a healthy life so we can get there [and read them]. But I think, in terms of my own work on Plath, I've done everything I've wanted to do.

James: One of the pieces I did really love was Snow Blitz, which is an amazing piece that was published in a magazine. It’s an amazing depiction of London and England of that period. I think we romanticise England—certainly we do here—but actually, England was quite a grim place, and there were lots of difficulties.3 And it’s amazing, particularly with her kind of American brain just going: what do you mean? Why can’t you just fix the pipes?

Peter: Why are the pipes on the outside of the house?!

James: Yeah, like, what are you doing? Overall, did she like England, or was she only here because Ted wanted to be in England?

Peter: I think she loved England. Part of it was because her husband was English, and that's where they met. It's where they married. It's where they probably had the best couple of years of their marriage. The period in the US from 57 to 59 is an interesting period. We don't have a lot of letters from that period because she was within distance of speaking to her Mom on the phone or seeing her in person. So there's a lot of stuff we're missing from that period in terms of an understanding of what they were doing and how they were living. But it was clear that Hughes didn't like being there.

James: Yeah Ted Hughes seems very English.

Peter: Yeah, he was. I think she was happy to go where he was going to be happy, and in part because she was acquiescent. But also, you know, he was the major breadwinner at the time, and if he felt like he was going to produce better in England, it's where they needed to be. But they also were the first place to give her a book contract for The Colossus, the first place to give her airtime on the radio, and things like that. She loved the BBC, and she saw opportunities there that did not exist for her in the US. So I do think she was really happy there. And I think that's a large reason why she didn't just run home after the marriage broke down.

James: That’s something I've often thought about. Why move to Devon? I mean, Devon is very nice, but why didn't she just go home with the two kids? It would be the, I suppose, logical option, one that a lot of people probably would take, which is to go home when your life is collapsing.

Peter: Part of it, I think, was she was probably hoping that things would calm down and he'd come back and they’d get back together. You see that in her letters, where some days she's totally done with him, but some days she completely misses him. So I just imagine it was an absolute roller coaster for her. And I think taking the children, she definitely did not want to be close to her mother. And I think that that was also a contributing factor as to why she decided to get out of Devon and move back to London, where at least there were people, there's civilization, or what she termed civilization, and all the distractions of the city that she really missed once they were settled at Court Green.

James: She's clearly got a very good journalistic style. Did she enjoy that kind of writing? Do you think that had she survived, that could have become quite a big part of her writing career?

Peter: I do. At the time that she died, she was in negotiations or whatever with the BBC to be on a programme called The Critics in May of 1963, and that seemed to be a programme that she was familiar with and that she enjoyed. All the New Statesman reviews that she was writing in the last couple of years, I think she thoroughly enjoyed doing. Not only did it pay a little bit, but she got free books and she reviewed tons of children's books, which was great. So she had free books that she had for her children's formative years. She wasn't really around for that, unfortunately, but at least they had them. I think she probably would have gone on to be quite a good book reviewer. Also works like Snow Blitz, Landscape of Childhood, and The All Round Image—that sort of nonfiction writing she would have just been excellent at.

James: Yeah, definitely. Like the London Review of Books, New Yorker, and Times Literary Supplement type of long essay, she would have been fantastic at.

Peter: Yeah, absolutely.

James: Why do you think that there's been no major adaptation of Plath's work? I mean, I mean a good one. I know that there was that thing with Gwyneth Paltrow, but there's been no majority like the film The Bell Jar. As far as I know, there's not been a major theatrical production. I know that previously Kirsten Dunst was going to direct one, but that either is in development hell or it's just gone away. Again, given how popular and now famous she is, it's kind of odd that there hasn't been one.

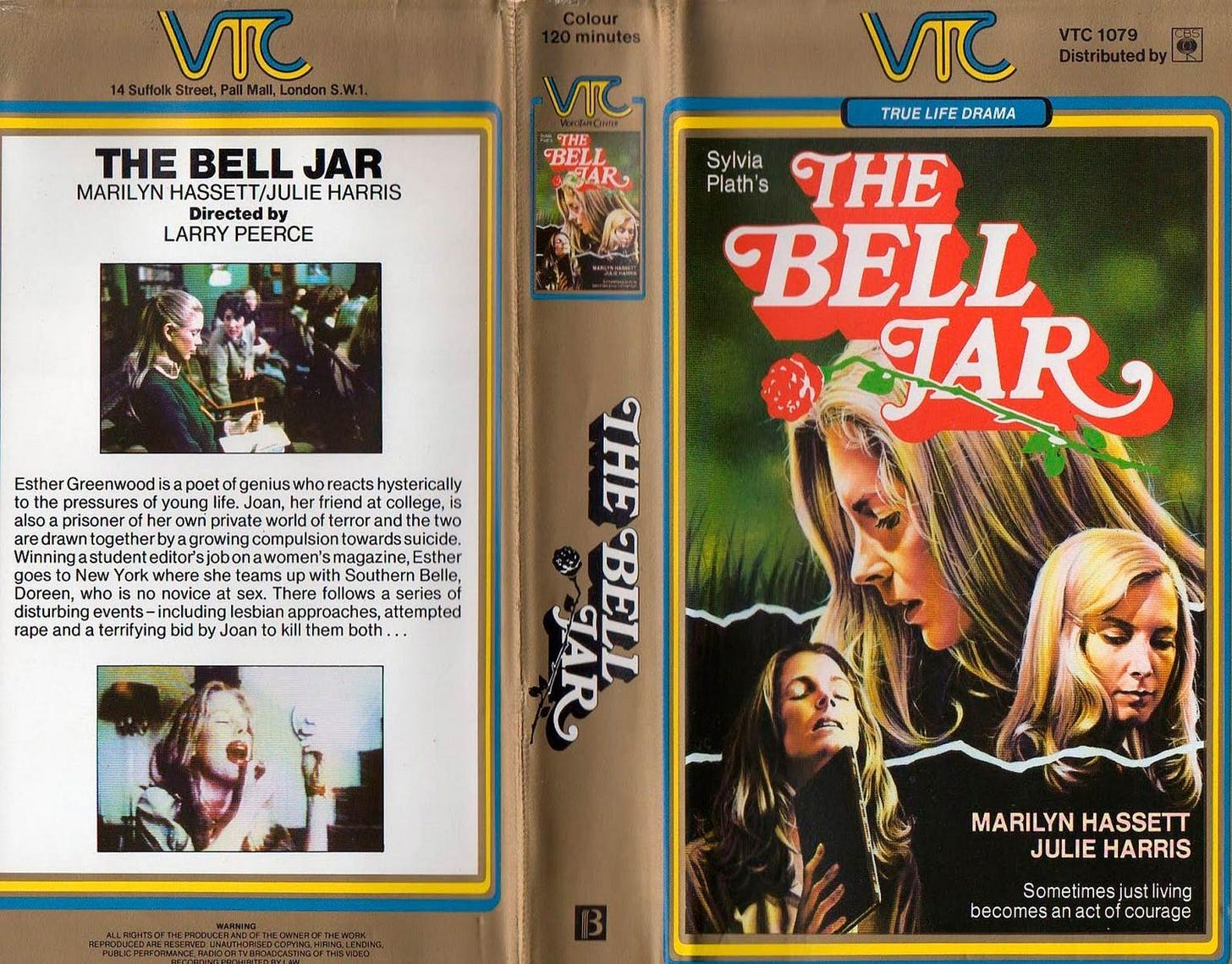

Peter: There was a film version of The Bell Jar that came out in 1979 in the US. It is so awful. You have to watch it, but do it drunk. So there's that one. And it was truly terrible. Then Julia Stiles had the rights to do it for a while in the US. They had a film script written, and they had some of the cast set, but then when the market crashed, they lost funding and momentum.

James: Typical.

Peter: Then Kirsten Dunst had it for a while, and Dakota Fanning was going to play Esther Greenwood, and I actually met them and gave them a tour of the Plath sites in the Boston area.

James: Oh wow, that must have been something.

Peter: [It was] truly amazing. I think in 2016 I did that. Then, a year or so later, there was another American actress called Frankie Shaw who had a brilliant idea, which was to do a Netflix series of The Bell Jar. So have it be, like, eight-hour-long episodes rather than a cinematic adaptation, in which case you could do the whole book and not really worry about what you're going to cut. But that ended up not happening. But periodically you hear smatterings that Kirsten Dunst still wants to do it or be involved, but I just don't know. I don't know where that stands. I would love to see something true to the novel be done because I think it's actually a very cinematic novel.

James: I'll finish with a kind of silly question. So you've got a T.A.R.D.I.S., you can go back in time, and you can have Plath read you one poem. What would you pick?

Peter: Oh, Jesus. I'd probably say The Moon and the Yew Tree.

James: Oh, interesting.

Peter: It's one of my favourite poems by her. I find it absolutely beautiful. She wrote it just as she was about to sign a contract for The Bell Jar with Heinemann. She was six or seven or so months pregnant. It was after a miscarriage, after her appendectomy, and so on and so forth. So much was about to happen. It's an amazingly beautiful poem. I would go back to the moment when she finished typing up the final copy because she was in her study in Court Green. Her study window looks out on the church and the Yew tree, and I'd like to sit there and look out the window while she reads it. That's what I'd like.

The Collected Prose of Sylvia Plath is available now:

https://uk.bookshop.org/p/books/the-collected-prose-of-sylvia-plath-sylvia-plath/7688686?ean=9780571377640

You can follow Peter’s writing on Plath at his website: https://sylviaplathinfo.blogspot.com/

His Twitter is: @sylviaplathinfo

I got this date wrong during the interview and changed it while editing. I’m only telling you this because I’m so postmodern that I haunt Jordan Peterson’s nightmares and confuse him in his dreams.

Look at this for literary goss.

And there are obviously not any problems in the country now. (satire).